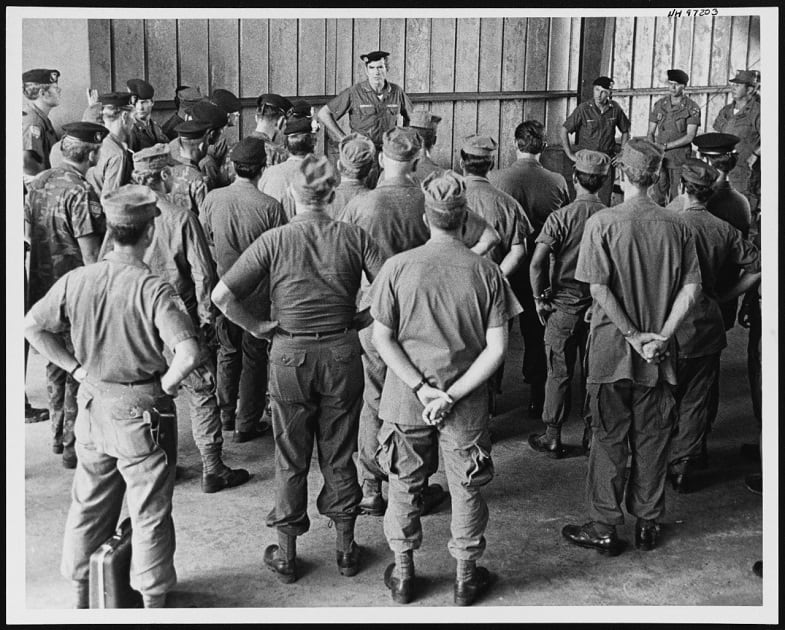

Cigar-chomping Army Gen. Creighton Abrams slammed the table during a briefing in Saigon. “Bullshit!” he erupted. That’s all he ever got from the Air Force, the four-star complained and stormed out.

It was November 2, 1968. Abrams, the top U.S. general in South Vietnam as head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, had just returned from a secret meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson. The president, still stinging from the North Vietnamese Army’s attacks during the Tet new year’s celebration in January, told the MACV commander: “Muster every [South] Vietnamese with a penis and get him into military uniform.”

Abrams held the Saigon conference to discuss a program that would eventually turn military operations over to the South Vietnamese so the Americans could withdraw, a strategy later called Vietnamization. The Air Force briefer had presented an eight-year transition plan that angered Abrams. After the general walked out, a pall fell over the briefing room.

Once Abrams returned, it was the Navy’s turn, and 47-year-old Vice Adm. Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt, the new commander of Naval Forces Vietnam, was determined to avoid the Air Force miscues. Zumwalt’s operation, which oversaw the Navy’s coastal and riverine forces (but not seagoing warships), reported to Abrams, and the admiral had been ready to present a three-year plan to the MACV commander but decided it needed some last-moment tweaking. “I told my briefer,” recalled Zumwalt in a 1996 interview, “wherever we had ‘may’ in the [briefing] slides, we would [substitute] ‘will.’”

Read more from HistoryNet:

- Lawrence Sperry: Genius on Autopilot

- Last Train Home

- Case of the Mysterious Lob Bomb

- The Storm Before the Storm

When other service representatives criticized Zumwalt’s “Accelerated Turnover to the Vietnamese” plan, Abrams cut them short: “Look, this guy’s the only one that’s got a plan.”

South Vietnam’s coast and interior waterways offered dismal prospects for Zumwalt’s plan. A 1964 study group headed by Navy Capt. Phil H. Bucklew found that the North Vietnamese were infiltrating the south with troops and supplies through three routes: the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ran through Laos and Cambodia; the South Vietnamese coast; and Cambodian ports that provided access to enemy sanctuaries in border towns. The Bucklew Report called for beefed-up coastal patrols but stressed that a coastal quarantine would fail unless inland river routes — especially along the border with Cambodia — were sealed.

Events soon overtook Bucklew’s recommendations. On February 16, 1965, a munitions-laden North Vietnamese trawler was discovered in Vung Ro Bay, on the central coast of South Vietnam, and sunk by airstrikes. The presence of an enemy trawler convinced MACV that the primary waterborne menace lay seaward, and the Navy initiated Operation Market Time to secure more than 1,000 miles of “blue water” along the coast. The operation was conducted by the Coastal Surveillance Force, designated Task Force 115 in July 1965, consisting of destroyers, Coast Guard cutters and the Navy’s patrol craft fast, or PCF, commonly known as swift boats.

The Navy didn’t altogether neglect the “brown water” rivers and canals of the interior. Initially lacking riverine vessels, it soon acquired some — in particular, the nimble patrol boat river, or PBR — and began Operation Game Warden in December 1965. The River Patrol Force, designated Task Force 116, prowled the Mekong Delta’s major rivers, a swampy portion of the delta on the edge of Saigon called the Rung Sat Zone, and the main water route into Saigon, the Long Tau shipping channel. In early 1967, the Mobile Riverine Force, Task Force 117, began using combined Army and Navy units to provide Game Warden with ground forces and air cover to stop Viet Cong infiltrators.

Although task forces 115, 116 and 117 crimped the infiltration, they also induced enemy countermoves and delivered diminishing returns. Perhaps most tellingly, the task forces failed to entirely shut down the water transport systems used by the Viet Cong to move supplies during the devastating, albeit ultimately unsuccessful, 1968 Tet Offensive.

“I don’t know what you are going to do,” Abrams told Zumwalt when they first met that September, “but I know what you’re doing now stinks.”

Zumwalt realized he had to inject new vigor into waterborne operations and devise a more effective strategy aligned with Abrams’ intention to switch from “search-and-destroy” tactics (hunting down the VC and killing them in large numbers) to “clear and hold” (pushing the VC out of an area and providing security to keep them out). He then had to transfuse that vigor and effectiveness into the South Vietnamese Navy.

Zumwalt recalled that one day in October 1968, as he stared at a map, it dawned on him that “there was water all the way along the Cambodian border,” which “made it possible — along several hundred kilometers — to install a blockade.” Zumwalt called his command team to Saigon, and they hammered out Operation Sealords, an acronym for Southeast Asia Lake Ocean River Delta Strategy. The broad objectives were to interdict enemy supply and communication routes, destroy enemy sanctuaries, open waterways to commerce and improve security for the South Vietnamese in select areas.

At Sealords’ heart was Task Force 194, which borrowed from task forces 115, 116 and 117. Zumwalt’s plan was bolstered by Naval Forces Vietnam’s resources, then at peak strength, with 38,000 sailors. Task Force 115 operated nearly 150 vessels including 81 swift boats; 116 deployed 258 patrol and minesweeping craft; and 117 boasted 184 vessels, 25 helicopters and 15 attack aircraft.

The Sealords strategy was built around boat patrols that would form blockades of rivers and canals to create barriers against enemy infiltration of the delta. The first barrier was established on November 2, 1968, when Mobile Riverine Force personnel launched a five-day assault along the Rach Gia-Long Xuyen and Cai San canals near the Gulf of Thailand in Operation Search Turn. That barrier lay well south of the border with Cambodia, a supposedly neutral country but one that nevertheless had Viet Cong and North Vietnamese bases. The operation killed enemy infiltrators and captured contraband in the area, but Sealords brass realized they needed to extend their barrier across the delta to be truly successful.

A can-do junior officer had already expanded Sealords’ operational horizon. On October 14, 1968, Lt. j.g. Michael R. Bernique, the 24-year-old skipper of Market Time’s PCF-3, was in Ha Tien, on the Gulf of Thailand close to Cambodia, when he learned from a local U.S. Army adviser that Viet Cong were setting up shop and forcing villagers to pay “taxes” a few miles up the Rach Giang Tanh, a canal hugging the border between South Vietnam and Cambodia. That waterway was off-limits to the Navy patrols because of its closeness to Cambodia, but Bernique, a beefy, balding Notre Dame graduate, assembled his five-man crew, got underway and soon, rounding a bend in the Rach Giang Tanh, ambushed the enemy.

“They were sitting on the bank collecting tax money,” remembered David Hemenway, an M16-wielding 20-year-old poised on PCF-3’s bow. “The civilians took off quick, so we had no problem shooting back.” M16 and .50-caliber gunfire dropped three VC revenuers as PCF-3 sped by — then reversed course. “When we came back, they ran,” Hemenway said. “We beached our boat and grabbed what we could as fast as we could.”

Recalled to Saigon, Bernique had some explaining to do to his superiors: “Half of them wanted to court-martial him, half wanted to give him a medal,” according to Hemenway. One Zumwalt aide informed Bernique that Cambodia’s Prince Norodom Sihanouk accused his crew of shooting innocents. “Well, you tell Sihanouk,” Bernique said, “he’s a lying son of a bitch.” That rejoinder (and the “very valuable information” the crew had captured) convinced Zumwalt that Bernique was “the kind of captain we need.” Bernique was awarded a Silver Star.

The Rach Giang Tanh, which the sailors now called “Bernique’s Creek,” formed the left (west) flank of a second Sealords campaign, Operation Foul Deck, whose right (east) flank was the Upper Bassac River. The east flank headquarters was a 700-ton “Yard Repair, Berthing and Messing” barge, YRBM-16, anchored off Chau Doc. Ten boats from the Navy’s River Division 552 conducted round-the-clock patrols west along the narrow straightaways of the Vinh Te Canal.

“There was an entrance to the canal at Chau Doc,” said Gordon Peterson, River Division 552’s senior patrol officer. “We’d usually go out in the evening and come back the next day, an overnight.” While river patrol boats policed the Vinh Te, swift boats, “assault support patrol boats” and monitors (28-ton armored craft reminiscent of Civil War monitors) guarded the Rach Giang Tanh. Foul Deck’s first months were routine. “We saw a lot of water buffaloes,” Peterson remarked. “Occasionally there’d be a firefight, but not too often.”

The relative calm disappeared on November 23, 1968, when the River Division 552 commander, 37-year-old Lt. Jack Berkebile, led a three-boat night patrol towards a suspected VC river crossing. Two days earlier in that area, Division 552 patrol boats were hit with heavy automatic weapons and rocket fire. “That night, I was assigned to go on patrol,” Peterson recalled, “but Jack said, ‘No, let me go.’ He enjoyed the patrols. I was in the YRBM operations area when we got word of a KIA. Somebody asked: ‘What’s the KIA’s name?’ Word came back the KIA was ‘Literary Zulu’ — Jack’s call sign. He took a B40 rocket right into the torso.”

With Search Turn and Foul Deck established, focus pivoted east to Parrot’s Beak, a menacing bulge of Cambodian territory that converged at its southern end about 25 miles west of Saigon. The area was bracketed by two Vam Co River tributaries: Vam Co Tay to the west and Vam Co Dong on the east. Because the branches flowed together in a Y-shape, the Sealords action was named Operation Giant Slingshot.

During Giant Slingshot’s opening months, sailors engaged in more firefights, captured more enemy fighters, confirmed more kills and destroyed more munitions and supplies than any interdiction operation before or after, according to Tom Cutler, author of “Brown Water, Black Berets.” But Giant Slingshot’s firefights also cost 38 U.S. sailors killed and 518 wounded. The fighting was so intense that the Navy limited the time its sailors served in the Giant Slingshot area.

Lt. John M. “Jack” Geraghty, executive officer of River Division 512, and his unit were rotated from the Bassac to Tra Cu on the Vam Co Dong early in 1969. “We relieved a group that got shot up pretty badly,” he said. Surviving the Vam Co Dong required new tactics. “At some point, we decided to do night ambushes,” Geraghty said. “We would pick a likely infiltration spot where there’d been activity or [we had intelligence] there would be something.”

Geraghty’s unit was moved to Chau Doc in June 1969 and relieved in Giant Slingshot by River Division 552. “Every patrol officer had his own philosophy of how to operate,” said Bruce McCamey, senior patrol officer for River Division 552. “At PBR school they would talk about patrolling [but] two PBRs coming down the river make a lot of noise — just asking for it. I preferred to pull my boats underneath the cover of the trees.”

One moonlit night McCamey spotted an enemy sampan paddling up the river. “I tried to get my cover boat’s attention but couldn’t,” he said. “I was going to lose the sampan, so I just opened up with the midship’s M60” machine gun. All of the sampan’s crew ended up dead in the river. The Americans carried away captured weapons and North Vietnamese Army intelligence.

Operation Barrier Reef, the fourth Sealords campaign, forged a link between the upper Mekong River and the Vam Co Tay across the Plain of Reeds. Because of the relatively long distance between the Cambodian border and Barrier Reef’s two primary waterways, the La Grange-Ong Long and Dong Tien canals, the area never had as much activity as the other zones experienced. But enemy infiltration did spike in mid-May 1969.

On May 12, River Division 552, operating out of Tan Chau on the upper Mekong under Lt. Tom Barnett (who had replaced Berkebile), learned that 500 enemy troops were massing nearby. As local forces battled onshore over the next days, patrol boats supplied heavy suppression fire. In the pre-dawn hours of May 17, the American boats went to a spot where they thought an enemy crossing would occur, remembered Frank W. Free, a 21-year-old gunner. “A clear night, but no moon. I was in the coxswain flat when engineman Carl Hoppy picked them up: three sampans, one close to beaching.”

The sampans were big, with probably 12 to 15 people aboard. Free went down through the radio compartment to get into his gun tub. Barnett was on the bow with an M16 and battle lantern, Free said. “I wasn’t anywhere near ready, [but] he turned the light on and yelled, ‘Come here!’ in Vietnamese. They all opened up. All I could hear was rounds going through the boat. Tom got hit and went down. Carl — he was on the M60 — finally got [the sampan occupants] to jump in the water. I suppressed fire from the bank. The cover boat started shooting illumination. Tom wasn’t really hurt — the round hit a magazine clip stored in his flak jacket.” When the boat finally tied up at base, the bilge alarm went off. “We had so many holes [that] we were sinking,” Free said. “They had to lift us out of the water and start patching.”

Although inland tributaries and canals were Operation Sealords’ primary battle spaces, coastal rivers flowing into the South China Sea from the Ca Mau Peninsula and into the Gulf of Thailand from the U Minh Forest also saw action. Those regions, thick with forests, swamps and VC, had largely been ceded to the enemy. However, during Sealords’ first six months, swift boats and Coast Guard cutters staged dozens of raids, killing, wounding or capturing more than 1,000 enemy and destroying huge weapon and supply caches.

As Sealords’ surprise factor faded, enemy forces (increasingly North Vietnamese regulars) laid ambushes from fortified bunkers, igniting some of the fiercest engagements swift boat sailors experienced.

On April 12, 1969, Hemenway, formerly aboard PCF-3, was helmsman on PCF-5, the lead boat in a flotilla on the Duong Keo, a river on the southeast tip of the Ca Mau Peninsula. Five boats carrying South Vietnamese troops had come in hours earlier, beached and let off their troops. Then the next eight swift boats arrived. The last was PCF-43, commanded by Lt. j.g. Don Droz. Onboard was Detachment Golf, Underwater Demolition Team-13, including Lt. j.g. Peter N. Upton. PCF-43 also carried 800 pounds of high explosives.

Upriver, Viet Cong ambushers had planted a cluster of fish stakes that “came up about halfway out from our starboard side,” Hemenway said. “We had to keep the boats to port. Just as we came around the bend they opened fire. We didn’t get a whole lot [of fire] in front, but we got a whole lot in back. We hit full bore because we were only doing about 10 knots.”

Enemy gunners singled out the heavily laden PCF-43. A B40 rocket-propelled grenade exploded on the boat’s fantail, killing the demolition team’s chief hospital corpsman, Robert “Doc” Worthington, and wounding several others. “I saw Worthington just virtually cut in half,” Upton said. Another B40 mortally wounded skipper Droz and his helmsman. PCF-43 careened out of control onto the north bank, its hull canted toward the river, directly athwart enemy emplacements.

The swift boat’s abrupt grounding momentarily disoriented the ambushers, enabling demolition team and boat survivors to establish a defense perimeter. As others fought from the boat’s slanting deck, Upton and two signalmen, Art Ruiz and Robert Lowry, grabbed the demolition team’s M60 and leapt from the bow to a firing position on the bank. Ruiz was seriously wounded by a grenade blast.

PCF-38, seventh in the file, tried to come to PCF-43’s rescue but took a B40 to its pilot house, wounding the skipper and crippling the steering system. Only the coxswain’s skillful throttle control enabled an escape. Alerted by radio, PCFs 5 and 31 rumbled into action. “We had a lot of wounded” on PCF-5, Hemenway said. “I was patching guys up while [skipper] Bill Shumadine was monitoring the radio. He told me, ‘We’re going back down.’”

PCF-5 got to the grounded boat before PCF-31 did. “We opened fire, strafed it all,” Hemenway said. Then the commander of 31 “told us to provide cover fire, and they pulled up next to the 43 and pulled all the guys off. Bill Shumadine then tried to tow the 43, but it wouldn’t budge, so the UDT team rigged the explosives. I could just see [43] blow to smithereens as we turned a bend in the river. It was something else.”

As brown water sailors fought on, Sealords grew and morphed, energized by ZWIs — Zumwalt’s wild ideas. In May 1969, after heavy Vam Co Dong losses forced the enemy to shift eastward to the Saigon River’s upper reaches, Zumwalt arranged to airlift six patrol boats 16 miles between rivers and established Operation Ready Deck there in October. In June, to promote commerce on the Ca Mau Peninsula, he established Sea Float, a base operating — in defiance of Viet Cong commandos and other predations — in the middle of the Cua Lon River. In September, an “advanced tactical support base” was anchored on the Ong Doc River near the U Minh Forest as headquarters for Breezy Cove, Sealords’ fifth and final campaign.

All along, resources and responsibilities were shifting to South Vietnam’s Navy, whose sailors were trained and integrated into U.S. crews. Local shipyards built replacements for patrol boats and swift boats. Beginning in early 1970, formal campaign control gradually passed to the South Vietnamese. By year’s end, South Vietnam’s Navy had mustered 32,000 officers and enlisted men as the U.S. Navy presence dwindled to a 500-man Naval Advisory Group.

Like any Vietnam War strategy — land, sky or water — assessments of Sealords depend on perspective. For front-line personnel, assessments were survival-oriented, short-term and specific. River Division 512 executive officer Geraghty said that in the Giant Slingshot area conditions “somewhat improved in the sense we didn’t have as many firefights towards the end.”

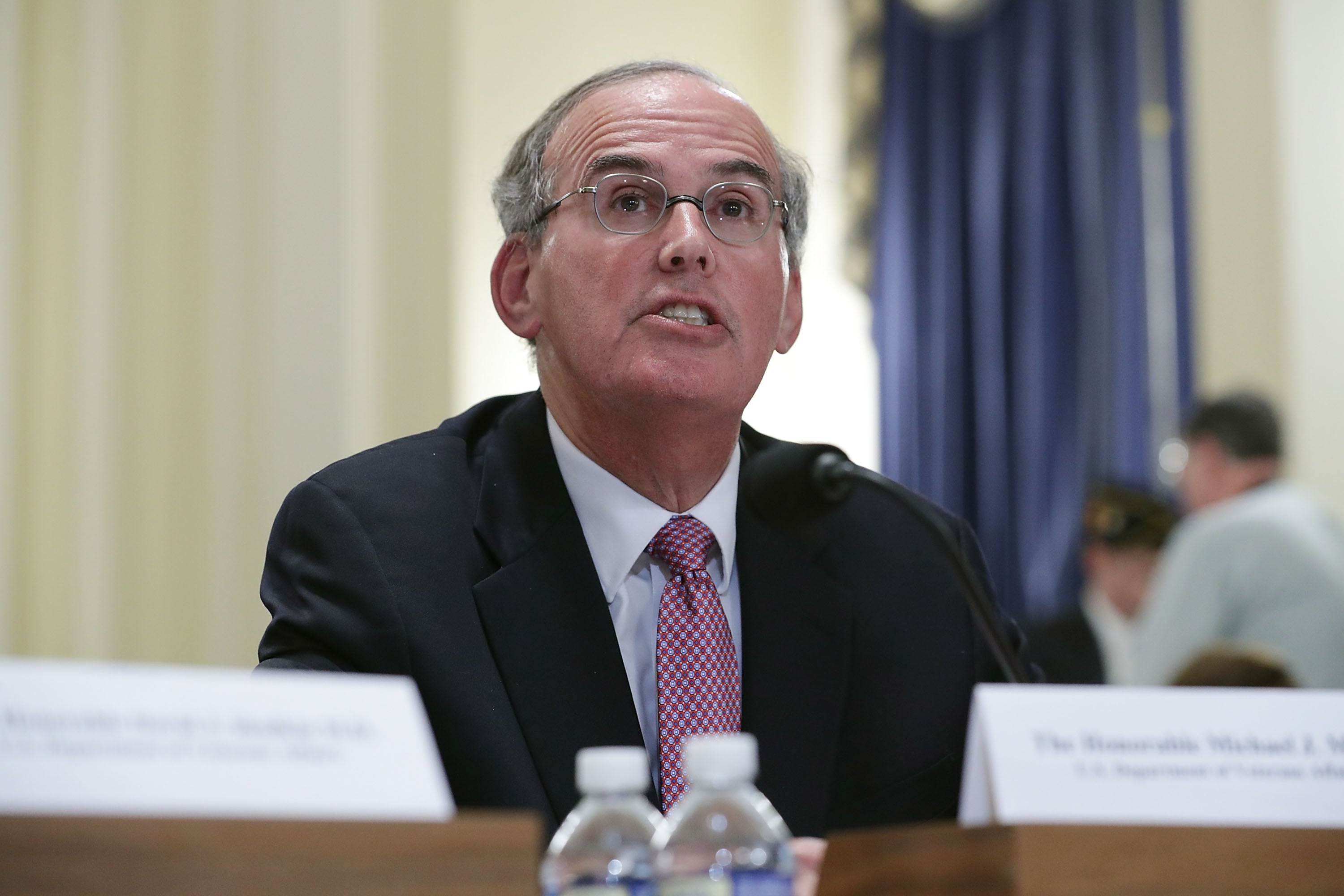

Vietnam veteran Edward J. Marolda, co-author of Combat at Close Quarters, takes a broader perspective. He rates Sealords a “temporary tactical success” for four reasons. “First, the hard fighting of American and Vietnamese sailors. Second, Admiral Zumwalt’s decisive leadership. Third, after taking a real drubbing during Tet ’68, the enemy were licking their wounds. Finally, the resources Zumwalt received for Vietnamization: more boats, lots of logistic facilities.” So impressed were Washington authorities with Zumwalt that he vaulted to chief of naval operations.

Marolda says Sealords’ success enabled an entire South Vietnamese army division to be moved out of the relatively quiet Mekong Delta and sent north to help stop an enemy advance on Saigon during the Communists’ 1972 Easter Offensive.

To be sure, “success went down when Americans turned over operations” he notes. “Also, the nature of the war changed.” As the North Vietnamese Army focused on artillery, armor and conventional troop forces to conquer Saigon in 1975, Marolda says, “the Delta became a backwater.”

This article was originally published in Vietnam Magazine, a Military Times sister publication. For more information on Vietnam Magazine, and all of the HistoryNet publications visit historynet.com.