The quote, “You did not join the military to get wealthy,” is often used to convey the idea that military service is about sacrifice and duty, rather than personal gain. While the exact origin of the phrase is unclear, it reflects a common sentiment that military service is a noble endeavor, undertaken for the sake of one’s country and fellow citizens, rather than for financial benefits.

Having said that, the members of our military must live in the society they serve, and be enticed to serve in the all-volunteer force. Thus, financial considerations, whether they be free college, free medical care, pay, bonuses, or retirement plans, all come into the mix when deciding to both join the military and remain in it.

RELATED

One of the most important, albeit at the time controversial, changes to military compensation has been the use of the Thrift Savings Plan, or TSP, as part of the Blended Retirement System. Allowing service members to hold TSP accounts ushered in change for how they saved for retirement. Rather than serve 20 years to receive a pension, service members could start saving for retirement well before, joining many other Americans who save through defined contribution accounts. Recent reports show a surprisingly high enrollment rate in TSPs, with nearly 85% of active-duty service members in the Blended Retirement System enrolled.

Despite the high enrollment numbers, the actual amounts invested remain low, at about $14,500 per account. Raising this amount should be in the express interest of Congress and military leadership, not only to increase our service members’ financial security but also to help ease our recruiting crisis.

There are three reasons why service members have stashed so little in their TSP accounts: First, their paychecks are generally small, especially among junior enlisted ranks; second, they are not eligible for the full government match until they reach two years of service; and three, the 5% government match contribution is simply not enough to create a retirement nest egg.

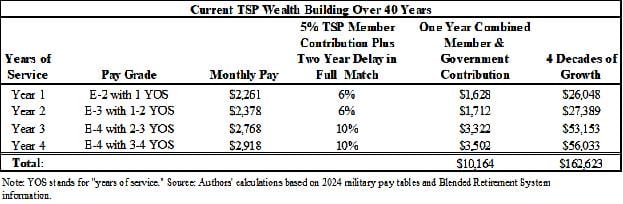

Over a four-year period, a junior enlisted soldier will go from making $2,261 per month as an E-2 with less than two years of service to $2,918 per month as an E-4 approaching four years of service. The table below shows how much wealth they can create in the current plan, assuming they make the 5% contribution into the Roth TSP and invest it in the C Fund at a 7.2% rate of return over 40 years.

While the IRS has a $23,000 limit for employee-only contributions and a $69,000 limit in combined employee/employer contributions, this service member falls far short of what is legally permissible. Additionally, not all service members take advantage of the TSP. We still have roughtly 15% of the force in the blended system not contributing.

While our junior enlisted may be low on savings at this point in their careers, they are rich in time and in a very low tax bracket, allowing their contributions to grow exponentially, potentially tax-free, over the decades.

So, why talk about this now? Because Congress is setting its sights on today’s recruiting crisis and is targeting a significant pay raise for junior enlisted service members. Better than being provided as a straight percentage increase, this raise could be structured in such a way to build wealth, and in doing so, become a shining example of how the private sector could perhaps reform these defined contribution plans.

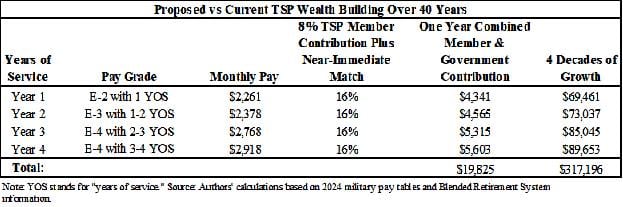

This proposal could proceed in four parts: auto-enrolling at 8%, increasing the government match to 8% immediately upon completion of basic training, removing the opt-out provision, and putting both the military members and the government’s contribution into the Roth TSP.

If these steps were taken, the service member would have about $317,000 in retirement savings over the same four decades of growth, as the table below demonstrates.

Of course, mandatory enrollment in the TSP would come with a trade-off. Service members would have less disposable income each month, as a portion of their pay would be automatically diverted to their retirement account. This could reduce their spending power and affect quality of life in the short-term. However, this trade-off could be mitigated with the current pay raise goal.

Under the guidelines of, say, a 15% raise, the additional funds could be split, with 7% being allocated to the new immediate and higher government match (7% plus existing 1%) and the remaining 8% to mitigate the effect of the higher auto-enrollment and dismantling of the opt-out provision. Finally, making the entire contribution to the Roth TSP will potentially save service members tens of thousands of dollars, if not more, when they retire.

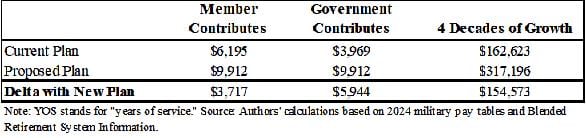

Taking these steps would have a tremendous effect on wealth creation. The table below shows that if this junior enlisted soldier contributes an additional $3,700 over their first four years, which is the difference between the current 5% and proposed 8% auto-enrollment amount, they would wind up with an additional $154,000 at retirement, all potentially tax-free.

The trade-off between the TSP and the pay raise is not a zero-sum game. Both are important components of the compensation package for service members, and both have positive effects on their financial well-being and morale. However, given that it is possible to have a much larger pay raise than proposed, coupled with the desire to build wealth amongst our junior enlisted, it is time to reconsider the balance between the two.

Increasing the auto-enrollment to 8%, raising the match to 8% and enabling it to start upon graduation from basic training, eliminating the opt-out provision, and depositing the contributions into the Roth TSP are fair steps to ensure every service member has a secure and comfortable path to wealth.

And, as an added bonus, it would make the military more competitive with the private sector, helping to ease recruiting challenges.

Retired U.S. Army Maj. Gen. John G. Ferrari is a senior nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute think tank. Ferrari previously served as a director of program analysis and evaluation for the service.