Once the hunters of the Atlantic ocean, the German wolfpacks by 1944 had become the hunted. Allied task groups dubbed “Hunter-Killer[s]” methodically attacked, scuttled and destroyed German U-boats, one by one.

On June 4, 1944, just two days before Operation Overlord, the Allies were once again on the prowl and achieved the near impossible — the U.S. antisubmarine Task Group 22.3 captured the Nazi submarine U-505 along with its crew, technology, encryption codes and a working Enigma cipher machine.

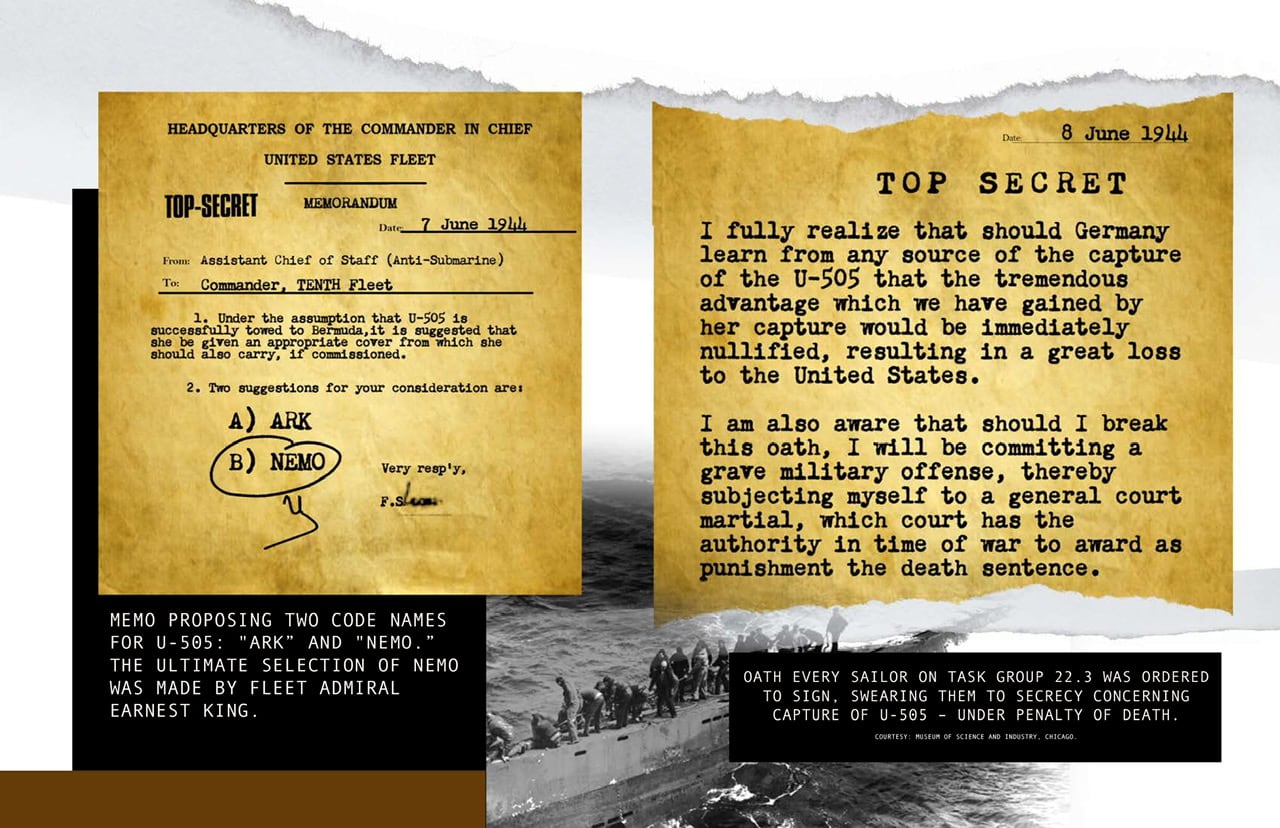

Incredibly, “Operation Nemo” was the first seizure of an enemy warship in battle since the War of 1812 and, for the first time since the war began in 1939, the U.S. and its allies were able to decipher German naval codes in real time.

Over 3,000 American sailors contributed to the hunt and successful capture of U-505, but it was nine ordinary American submariners who finished the job.

After examining these feats in his latest work, “Codename Nemo: The Hunt for a Nazi U-Boat and The Elusive Enigma Machine,” Charles Lachman, author and executive producer of Inside Edition, sat down with Military Times to discuss the cat-and-mouse game of hunting U-505 and the nine-man boarding party that changed history.

Can you discuss how this book came to be? You evidently had a serendipitous encounter at a museum in Chicago.

My wife and I were visiting our daughter one Thanksgiving a few years ago, and her boyfriend at the time wanted to entertain the parents. He took us to the Museum of Science and Industry. It’s one of these great museums where you can fiddle with stuff and it teaches science and American history from an industrial point of view.

The highlight is you go down to this cavern in the basement and there’s the U-505 just sitting there. I had never heard the story before. Maybe if you’re in the U.S. Navy it’s a familiar story, but to the layman it was mind blowing to see this massive Nazi U-boat in a basement on exhibit at a museum in Chicago some 80 years later.

I was just instantly drawn to it. I turned to my wife and said, “This is a book.”

Looking through the library material I quickly realized I was finding untapped sources of material from the archives in the museum. They were very generous about opening it up to me. I was also able to find and reach out to descendants of the U.S. sailors who volunteered for the mission. I opened up the story from the point of view of the German sailors as well. So, it’s kind of structured as a cat-and-mouse game between the Americans and the Germans.

How did the seizure of U-505 differ from, for example, the British seizure of the German U-110 sub in May 1941?

The Allies had possession of a couple German U-boats, so they had a good sense of what was inside. Most times, however, the Germans had enough time to destroy the Enigma machine and make sure that the secret code books were also destroyed.

The genius of this raiding party was that they were able to capture the long sought after Nazi codebooks and an intact Enigma machine.

This proved to be of great intelligence and value to the Allied war effort.

The U-505 had a pretty unlucky tenure prior to its capture. It’s second captain, Peter Zschech, notoriously committed suicide in front of his crew. How did you balance the German vs. American narrative?

I tried to alternate each chapter. Even though the Americans and the Germans did not know that destiny would bring them together on June 4, 1944, in a sense, it was inevitable.

It was important for me to include the German sailors’ point of view, for a couple of reasons: For the narrative, but also it was just fascinating to see how they saw the war going, how convinced they were of Germany’s ultimate victory, right up until the unconditional surrender in 1945.

And yes, the suicide of the of the captain was an extraordinary event. The U-505 had the reputation of being a hard luck ship. Its war record was not particularly distinguished, and there’s no question that the suicide of Peter Zschech became an important factor in the submarine’s history. It led to a lot of dysfunction on the ship when they needed discipline the most.

On June 4, 1944, instead of scuttling the vessel — you don’t give up the ship, right? — the German sailors fled for their lives. From the German point of view these men should have done their duty and scuttled the ship so as to not risk it getting into American hands. But from the Allied side, thank goodness they failed in that mission.

Lt. Albert David is the only Medal of Honor recipient from the Battle of the Atlantic. How did that come to be?

In 1999 several of the men who were still alive sat down for interviews at the museum, which are now archived. Lt. David’s story in particular is such a sad one. As you pointed out, he was the only recipient of the Medal of Honor in the Battle of the Atlantic — which was a major gripe for sailors in the region.

The one ironic aspect of his story is that he was not supposed to be the first American to go down the hatch for which he earned the Medal of Honor. He pulled another sailor aside and said he would go first. When they boarded the vessel they didn’t know what to expect. They were aware, through Navy intelligence, that the Germans had the capacity to set 14 detonation devices scattered throughout the boat. So, they thought they were walking into a ticking time bomb.

So, here’s this kid from Missouri, armed with only a Tommy gun, who decided to risk his life first. He decided to take command — and not for the glory, but he was willing to sacrifice himself.

The other guys were just regular Americans. Most of them were volunteers. They were kids. One of my favorite characters in the book is Wayne Pickels, a high school quarterback from Texas. He started off as a cook and ended up serving on this mission. He kept a diary throughout his Navy career, so that already gives great insight into his service.

The other thing that struck me was how many of these guys were first-generation Americans. A lot of them were born in Poland. They volunteered for the Navy because they wanted to get even with the Germans for invading their country.

By 1944 the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic had turned in favor of the Allies. How did the capture of this particular German sub help expedite the end of WWII?

It was absolutely critical. The Brits were the first ones to decipher the German naval code through the extraordinary decoding method they developed, but that took hundreds of hours to decode the ciphered messages. The value of capturing the U-505 was that is enabled us to read U-boat messages in real time — as fast as the Germans received them.

That freed up an estimated 13,000 hours of precious decoding computer time, which was critical in those all-important weeks following the D-Day invasion. They also obtained the navy cipher that was going to go into effect on July 15, 1944, laying out the settings for every U-boat and Nazi surface ship in their fleet.

The German navy code changed every two weeks for security purposes, so it was an extraordinary goldmine of material.

It may not have shortened the duration of the war, but it’s worth pointing out that 300 U-boats were sunk following the capture of U-505. Not all of those can be attributed to the intelligence windfall, but certainly many of them can.

What happened to the German submariners who were sent to Louisiana as POWs?

That was one of the most fascinating parts of the story I found in my research. There was the chase, the capture and the aftermath. The aftermath I found just as fascinating. For security purposes, the Americans did not notify the Germans about the capture of these men as it risked endangering the fact that we had the codes.

So, the Americans admittedly violated the Geneva Conventions by deliberately failing to inform the International Red Cross that these German sailors were prisoners in a POWs camp in Louisiana. Their families in Germany were notified by the Nazi government that they were presumed missing an action — which meant most likely dead since they were in the submarine service.

The German sailors — some of whom were hardcore Nazis — were kept isolated in this POW camp. They were not allowed to mingle with the other Germans. It was only after 1945 that their family members were notified that they were still alive.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.